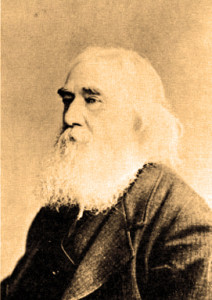

Lysander Spooner was not just a brilliant scholar; he was a great writer. He wrote the three greatest paragraphs ever written on trial by jury.

The three paragraphs introduced his readers to his brilliant essay/book Trial by Jury in the nineteenth century:

For more than six hundred years — that is, since Magna Carta, in 1215 — there has been no clearer principle of English or American constitutional law, than that, in criminal cases, it is not only the right and duty of juries to judge what are the facts, what is the law, and what was the moral intent of the accused; but that it is also their right, and their primary and paramount duty, to judge of the justice of the law, and to hold all laws invalid, that are, in their opinion, unjust or oppressive, and all persons guiltless in violating, or resisting the execution of, such laws.

Unless such be the right and duty of jurors, it is plain that, instead of juries being a “palladium of liberty” — a barrier against the tyranny and oppression of the government — they are really mere tools in its hands, for carrying into execution any injustice and oppression it may desire to have executed.

But for their right to judge of the law, and the justice of the law, juries would be no protection to an accused person, even as to matters of fact; for, if the government can dictate to a jury any law whatever, in a criminal case, it can certainly dictate to them the laws of evidence. That is, it can dictate what evidence is admissible, and what inadmissible, and also what force or weight is to be given to the evidence admitted. And if the government can thus dictate to a jury the laws of evidence, it can not only make it necessary for them to convict on a partial exhibition of the evidence rightfully pertaining to the case, but it can even require them [*6] to convict on any evidence whatever that it pleases to offer them.